Sizing Up Types in Rust

When learning Rust, understanding the difference between statically and dynamically sized types seems critical. There are some good discussions out there already (e.g. here and here). Whilst these explain the mechanics, they didn’t tell me why its done like this in Rust. The articles made sense, but I was still confused! Eventually I had my “eureka” moment, so I figured I should share that.

Getting Started

I’m a C/C++/Java programmer (amongst other things) and the basic idea

of a statically- versus dynamically-sized type seemed pretty

straightforward: A statically-sized type is one whose size is known at

compile time; and, a dynamically sized type is everything else. Easy

as! For example, an int is statically sized in Java (i.e. because

its a 32-bit two’s complement integer):

int x = 10;

On the other hand I figured an array int[] in Java is dynamically

sized (i.e. because we cannot determine how many elements it contains

at compile time):

int[] xs = new []{256,15};

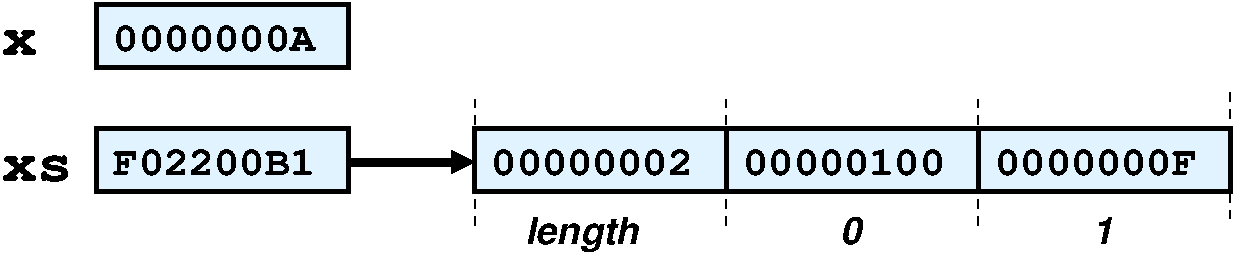

At some level, this all makes sense … but, unfortunately, it is completely wrong! In fact, an array in Java would be considered statically sized in the terminology of Rust. A diagram helps shed some light on this:

Its pretty easy to see that the size of x is known at compile time,

but what about xs? Well, yes, it is known at compile time — its

the size of a pointer (which I’ve just assumed is 32bits above for

simplicity).

Confusion Dawns

Now, we fast forward to a moment early in my journey to learning Rust. I’m writing a program, and I want an array to hold some data (like in Jave above). I think no problem, Rust has arrays — I’ve seen them! After some Googling, I find this:

“An array is a collection of objects of the same type

T, stored in contiguous memory. Arrays are created using brackets[], and their length, which is known at compile time, is part of their type signature[T; length].”

That remainds of C where we have int[N] and int[] for arrays, so I

figure something like [i32] makes sense. And, of we go down the rabbit hole …

fn main() {

let xs : [i32] = [1,2,3];

}

But, Rust is complaining about expecting a slice [i32] but finding

an array [i32;3]. But, I don’t want something complicated like a

slice … I just want an array!

After a bit more playing around, I notice that I can’t even compile this:

fn main() {

let xs : [i32];

}

The Rust compiler complains that xs doesn’t have a size known at compile-time. This is all pretty confusing. An array is an array,

right?

Digression

Most C programmers know the language is not consistent around arrays, and workaround this without even noticing. This little example illustrates:

void main(int argv, char** args) {

int x = 0;

int y[] = {1,2,3};

printf("x=%dbytes\n",sizeof(x));

printf("y=%dbytes\n",sizeof(y));

f(xs);

}

void f(int z[]) {

printf("z=%dbytes\n",sizeof(z));

}

On my machine, running this code gives the following output:

x=4bytes

y=12bytes

z=8bytes

That is curious … xs and ys have the same type but different

sizes! What’s going on? The type of ys is really equivalent to

int * (in that position) whilst the type of xs is really int[3]

(in that position). In fact, gcc rather nicely warns me about this:

‘sizeof’ on parameter ‘ys’ returns sizeof ‘int *’

Somehow C is trying to hide the differences between array

representations. We might say xs has an inline representation,

whilst ys has a pointer representation.

At least Java is more consistent as an array always has a pointer

representation. Still, int[] is not really an array in Java —

it’s a pointer to an array.

Enlightenment

Somewhere along the line, the penny dropped. I’m not sure what helped

in the end (though it wasn’t something I read). The problem is

exactly my background in C/C++ and Java! I’m just so used to

assuming an array is actually a pointer to an array. In Rust, an

array (e.g. [i32]) really is just an array. If you want a pointer

to an array, then you need a slice (e.g. &[i32]). Unlike C, Rust is

not trying to hide anything. And, unlike Java, it let’s you work with

both representations. This is progress!

Follow the discussion on Twitter or Reddit