Formalising Flow Typing with Union, Intersection and Negation Types

The Whiley language takes an unusual approaching to static typing called flow typing. This helps to give Whiley the look-and-feel of a dynamically typed language. The key idea behind flow typing is to allow variables to have different types at different points in a program. For example, consider the following code written in a typical object oriented language (i.e. Java):

public class Square {

private int x, y, len;

...

public boolean equals(Object o) {

if(o instanceof Square) {

Square s = (Square) o;

return x == s.x &&

y == s.y &&

len == s.len;

}

return false;

} }

What is frustrating here, is that we need to cast variable o to an entirely new variable s. The condition o instanceof Square asserts that variable o has type Square — and, the compiler should really be able to exploit this to avoid the unnecessary cast.

In Whiley, the compiler is able (amongst other things) to exploit type tests in this manner. For example, consider the following Whiley program:

define Square as { int x, int y, int len }

define Circle as { int x, int y, int radius }

define Shape as Square | Circle

boolean equals(Square s1, Shape s2):

if s2 is Square:

return s1.x == s2.x &&

s1.y == s2.y &&

s1.len == s2.len

else:

return false

In this example, no casting is necessary for variable s2 as the Whiley compiler knows it has type Square when the condition s2 is Square holds. An interesting question is: what type does s2 have on the false branch? Well, clearly, it is not a Square. And, that’s exactly how it’s implemented in the compiler — using a negation type. A negation type ¬T represents a type containing everything except T. In our example above, the type of s2 on the false branch is Shape & ¬Square. Here, T1 & T2 represents the intersection of two types T1 and T2. Thus, Shape & ¬Square represents everything in Shape but not in Square.

Subtyping Semantics

In building a compiler, it’s obviously important to develop algorithms for manipulating the types being used. In this article, I want to focus on the algorithm for subtyping. This simply reports whether or not a type T1 subtypes a type T2, denoted T1 <= T2. Based on the description given so far, one has an intuitive understanding of types as sets. That is, a type T represents the set of values which can be held in a variable declared with type T. In this way, we can think of T1 being a subtype of T2 if the set of values represented by T1 is a subset of those represented by T2.

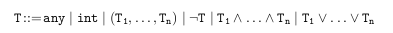

We now begin to formalise more precisely what types in Whiley mean (i.e. their semantics). We use the following language of types, which is a cut-down version of those found in Whiley:

Here, any is the type containing all values, int is the type of integers, (T1,...,Tn) is a tuple type, ¬T is a negation type, T1 /\ T2 an intersection type (written T1 & T2 in Whiley source syntax), and T1 \/ T2 a union type (written T1 | T2 in Whiley source syntax).

To accompany our language of types, we need to define what constitutes a value in the system:

Here, v represents a value which is one of two possibilities: either it is an integer, or it is a tuple value the form (v1,...,vn). Using this we can give a semantic interpretation of types in our language:

Here, we have defined a way to construct the set of values represented by a given type T. Whilst this may all seem rather mundane, it provides the necessary foundation for the subtyping algorithm.

An (Incomplete) Subtyping Algorithm

The subtyping algorithm is intended to determine when a type T1 is a subtype of a type T2. Or, equivalently, when the set of values represented by T1 is a subset of those represented by T2. The algorithm is surprisingly difficult to get right, and it has taken me sometime to develop. The following represents a good attempt to capture the algorithm and is presented as a series of recursive “type rules” covering the different possible forms of T1 and T2:

Under these rules, we can for example show that (int,int) is a subtype of (any,any) and, likewise, that (int,int)is a subtype of (int,any)|(any,int).

The real challenge with the above subtyping rules is: how do I know they are right? Obviously, I want to be sure that the type checking algorithm in my compiler will work as expected. But, it’s rather difficult to decide this just by staring at the rules. We need to break the problem down and we do this using the following notions of soundness and completeness:

Soundness. If the algorithm decides

T1subtypesT2, then it must follow that every value inT1is also inT2.Completeness. If every value in

T1is also inT2, then the algorithm must decide thatT1subtypesT2.

In fact, the above rules can be shown as sound. However, they are not complete. For example, we cannot show that any is a subtype of int | ¬int — a fact which is indeed true under our semantic interpretation.

Fixing the Subtyping Algorithm

Now, the question is:

Is there a sound and complete algorithm for subtyping testing in this language and, if so, what is it? The first part of the question (i.e. existence) was already shown by Frisch, Castagna, and Benzaken in their excellent (albeit complicated) paper.

The second part of the question (i.e. finding an actual algorithm) is also very important for me since I’m implementing an actual compiler. To figure this out, I went back to the drawing board several times and, finally, found a reasonable algorithm which is discussed here:

- Sound and Complete Flow Typing with Unions, Intersections and Negations. David J. Pearce. In Proceedings of the Conference on Verification, Model Checking, and Abstract Interpretation (VMCAI), 2013 (to appear) [PDF]

I won’t go into all the details here since its quite involved and the paper does a good job explaining things. However, the key idea is to represent types in a “special form” such that we can easily perform the subtype tests. The challenge is then to convert any given type T into its corresponding “special form”…

That’s all for now!