Implementing Structural Types

Introduction

Over the last few months, I’ve been working on the type system underpinning Whiley. A key feature is the use of structural typing, rather than nominal typing, and I’ve blogged about this quite a bit already (see [1][2][3][4]). Over the weekend, I finally found time to work through all my thoughts and turn them into code!

So, after making it all work with my existing system, I finally realised it would really really help to redesign the way types are represented in the compiler…

Recap

The main data types in Whiley are the primitives (e.g. null, int, real, etc), collections (e.g. [int] or {real}), records (e.g. {int data, Link next}) and unions (e.g. int|[int]). A good illustration is the following:

define LinkedList as null | {int data, LinkedList next}

define NonEmptyList as {int data, LinkedList next}

int sum(NonEmptyList ls):

if ls.next == null:

return ls.data

else:

return ls.data + sum(ls.next)

What’s interesting is that we can explicitly prohibit summing an empty list (of course, we could just return 0 for an empty list, but that wouldn’t make such an interesting example).

To type check this example, the compiler must show that NonEmptyList is a subtype of LinkedList. This turns out to be a significant challenge! Another big challenge is that of type minimisation:

define LinkedList as null | {int data, LinkedList next}

define InnerList as null | {int data, OuterList next}

define OuterList as null | {int data, InnerList next}

LinkedList f(OuterList ls):

return ls

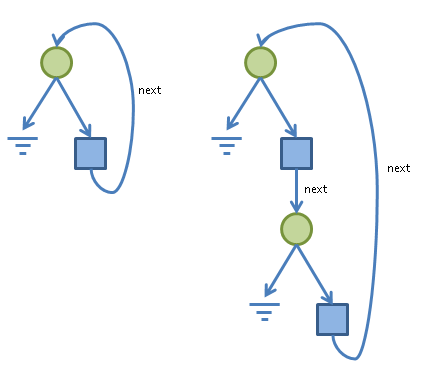

To type check this example, the compiler must show that LinkedList is structurally equivalent to OuterList. The following diagram illustrates this nicely:

Here, circles represent unions (e.g. T1 | T2), whilst squares represent records (e.g. { int data, ... }). The type on the left corresponds with LinkedList, whilst that on the right corresponds with OuterList (note: I’ve left off the data field from the diagrams as it’s not important here).

From the diagram we can see that, whilst the two types aren’t identical, they encode the same “structure” — but how can the compiler prove this?## Bad Idea My initial approach to implementing these types in the Whiley compiler was the most obvious one: encode them as trees using recursively defined data types. In Java this might go something like this:

class Int implements Type { ... }

class Real implements Type { ... }

class Set implements Type { Type element; ... }

class List implements Type { Type element; ... }

class Record implements Type { Map<String,Type> fields; ... }

class Union implements Type { Set<Type> fields; ... }

class Recursive implements Type { String name, Type body; ... }

This is mostly straightforward except for the way recursive types are defined. In this case, an instance of Recursive indicates the start of a recursive type and this is terminating by a matching instance where body == null. For example, we create our LinkedList type as follows:

// first, create internal record

HashMap<String,Type> fields = new HashMap<String,Type>();

fields.put("data",new Int());

fields.put("next",new Recursive("X",null));

Type record = new Record(fields);

// finally, put it altogether

Type LinkedList = new Recursive("X",new Union(new Null(),record));

This seems reasonably straightforward, and the type can be easily turned into a string such as "X<null|{int data, X next}>". We’d also probably want to use the flyweight pattern to avoid creating lots of identical types.

So, what’s the problem then? well, there are a number of issues. Firstly, we need to ensure that instances of Recursive don’t have name clashes which causes unexpected variable captures (admittedly, this isn’t too hard to do). Secondly, we need to ensure that Recursive variable names are not significant (i.e. that X<null|{int data, X next}> is identical to Y<null|{int data, Y next}>). Again, this is doable … but it starts to get complicated.

The final (and most significant) issue with this approach is that, in order to perform type minimisation, we need to view the type as a graph (see e.g. the diagrams above). Implementing types using the natural recursive tree decomposition makes it difficult (but, again, not completely impossible) to do this.

The bottom line is that, in my experience, implementing structural types like this just makes things harder than they need to be.

Better Idea

The main problem with the above approach is that we end up with these ugly instances of Recursive all over the place. The tree decomposition is trying to hide the fact that our types are graphs, not trees.

In my new system, things look quite different:

class Compound { Node[] nodes; ... }

...

private static final byte K_NULL = 2;

private static final byte K_BOOL = 3;

private static final byte K_INT = 4;

private static final byte K_RATIONAL = 5;

private static final byte K_SET = 6;

private static final byte K_LIST = 7;

...

private static final byte K_RECORD = 10;

private static final byte K_UNION = 11;

...

private static final byte K_LABEL = 13;

class Node { int kind; Object data; }

In this representation, a type is made up of one or more Nodes. Each node stores its kind, and also provides a data field for identifying its children. For primitive types, the data field is null, whilst for sets and lists it is an Integer (which identifies the child node). For records, it’s a Map<String,Integer> which identifies the child node for each field. Finally, for unions, the data field is a Set<Integer>.

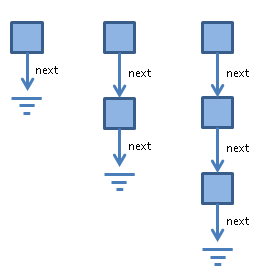

The following illustrates how this looks for our LinkedList example:

The nice thing about this is that we no longer need explicit Recursive instances. Thus, variable renaming and variable capture are impossible by construction. Futhermore, the graph representation is explicit and, hence, the type minimisation algorithm (see below) is easy to implement.

Nice Interfaces

The downside with the graph-based representation of types is that it is quite “low-level”. To simplify things from the users perspective, we can also provide special classes to make manipulating Compound types easy. For example:

class Int extends Compound { ... }

class List extends Compound { Type element() { ...} }

class Record extends Compound { Map<String,Type> fields() { ... } }

These classes provide methods which return newly created instances of Type by extracting them from their underlying structure using a depth-first search. In this way, the user never has to interact with Compound structures directly … which will be a relief for them! (note: of course, we need to carefully ensure the root node’s kind matches the actual subclass of Compound).

Type Minimisation

Having covered the representation of types, it’s interesting to see how the type minimisation algorithm proceeds. Essentially, there are two stages:

Constructing the subtype matrix.

Merging equivalent nodes, and eliminating subsumed nodes.

The following example illustrates the subtype matrix:

In the matrix, entries in dark gray are true and those in light gray are false. We can determine whether node X is a subtype of node Y by checking column Y in row X. For example, node 2 is a subtype of node 4. Once we have the subtype matrix, it is fairly easy to identify nodes which are equivalent — namely, those which are mutual subtypes (e.g. 0≡4 and 2≡6).

To construct the subtype matrix, we initially set every cell to true. Then, we cross-off all subtype relationships which are obviously incorrect (e.g. node 5 cannot be a subtype of node 3, since null isn’t a subtype of int). This may, in turn, invalidate other subtype relationships — and we keep crossing them off until there aren’t any left (i.e. until we’ve reached a fixed point).

With the subtype matrix constructed, we can identify and merge equivalent nodes (which, for example, reduces OuterList to be identical to LinkedList). Similarly, we can eliminate subsumed nodes — e.g. in the type int|real, the int node is subsumed by the real node, letting us reduce int|real to real.

Completeness. An interesting question is whether or not the algorithm for minimising types described above is complete. That is, whether or not there are types which could be minimised, but are not by the algorithm. It occurred to me, whilst I was implementing this, that the code was very similar to that for checking graph isomorphism. In fact, it’s easy to see that we can encode any graph using my type representation — which makes me think what we’re doing here is similar, or identical, to the subgraph isomorphism problem. In turn, this makes we believe there are examples which it will not minimise (e.g. those equivalent to cubic graphs are a particular problem for partition-based graph isomorphism algorithms).

Canonical Forms. Another interesting question is whether or not we can determine a canonical form for a given type. Again, this reminds me of the graph isomorphism problem, where the most successful solutions (e.g. Nauty) operate by computing the canonical forms for their input graphs — and, once they have this, testing whether they are isomorphic is easy!

Java Code

My Java implementation of this structural type system can be found here. It’s a little bit more optimised than my description above, but it’s otherwise pretty much identical. Let me know if you find any bugs …